The neon-noir fantasia from Nicolas Winding Refn, and the Danish director of Drive, Bronson and the Pusher trilogy, is a modern fairy-tale of beauty as a beast, a horror-inflected, high-fashion fable replete with wicked witches and big bad wolves ready to devour a flaxen-haired youth in the wild woods of Los Angeles. Less Prêt-à-Porter with teeth than The Company of Wolves from hell and in heels, it offers a bloody chamber of symbolic provocations (lunar cycles, occultist trappings) cooked up by a film-maker taking weekly tarot readings from the Chilean surrealist Alejandro Jodorowsky and driven by an intoxication with the superficiality of the photographic image.

Swooningly filmed by Natasha Braier, The Neon Demon puts overtly ludicrous flesh on a satirical script co-written with the playwrights Mary Laws and Polly Stenham, bringing a Jacobean Ab Fab edge (“sweetie, plastics is just good grooming”) to the poisoned apple proceedings on which Refn feeds as hungrily as any spellbound princess.

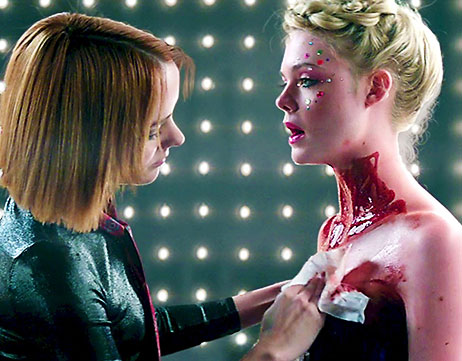

We open with Elle Fanning in an electric-blue dress, reclining upon a pale couch, drenched in crimson blood. Is it a crime scene or a fashion shoot? As the widescreen drama glides between the catwalk and the morgue, all flashbulbs appear equally morbid. Jesse (Fanning) is the 16-year-old ingenue (“when someone asks, say 19”), newly arrived in scary LA, who is told: “Don’t worry, that old deer-in-the-headlights thing is exactly what they want.” And it is. Amid a sea of battle-hardened smiles and dead-eyed robotic faces (think The Stepford Wives meet The Terminator), her youthful looks are a fetishised object of hardly obscure desire.

Yet soon, Jesse’s wide-eyed innocence turns to razorblade smiles, as the titular demon (represented by the kind of hexy prisms that once delighted Aleister Crowley and Kenneth Anger) works its dark magic. At a party that looks like a Gaspar Noé remake of Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, Jesse is seduced by the image of a bondaged woman levitating; later, on the catwalk, she passes through the looking glass into a narcissistic underworld, prophetically protesting: “I’m not as helpless as I look.”

For all its shimmery surface modernity, this story about the commodified consumption of youth is as old as the hills, a carefully choreographed carnival of voyeurism in which corruptible beauty is “the only thing” and every look comes with daggers. Motel rooms are stalked by beasts both real and metaphorical (Keanu Reeves giving good creep) and photographers are indistinguishable from serial killers (shades of Eyes of Laura Mars). But while Jesse may faint like Sleeping Beauty, with rose petals falling around her goldie locks, it’s her own image that grabs her by the throat. Mirrors are everywhere, to be stared into, scrawled upon, kissed and smashed. And the more Jesse looks, the more she sees nothing but herself…

At times The Neon Demon plays like an exposé of this cruel fashion cattle market, with models stripped to humiliating (rather than titillating) underwear, forced to endure the walk of shame under unforgiving gazes. Elsewhere, it doesn’t so much dip as dive deep into the waters of exploitation, with soft-core sapphic shower scenes and bloody baths evoking the spectre ofErzsébet Báthory, immortalised in Peter Sasdy’s campy Countess Dracula and Walerian Borowczyk’s Immoral Tales. Sliding into grand guignol, the primary colours and pointed objects evoke the 70s cinema of Dario Argento, with outré overtones of Lucio Fulci or Ruggero Deodato. A witchy image of Jesse splayed against a wall listening to a scene of sexual violence evokes Britt Ekland’s pagan dance from The Wicker Man, while Cliff Martinez’s sensuous music has something of the pulsating synth menace of Tangerine Dream’s Sorcerer score.

While Fanning’s Jesse may be the face of The Neon Demon, Jena Malone’s Ruby provides its dark heart – a makeup artist who divides her time between painting the faces of the living and the dead. In already notorious scenes that recall the demon birth of Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession and the controversial climax of Lynne Stopkewich’s Kissed (via Jörg Buttgereit’s Nekromantik), Malone proves herself to be a fearlessly “out there” performer, even as her director succumbs to his most unabashed schlocksploitation urges.

And therein lies the key. Although some have seen The Neon Demon as a divisive companion piece to 2013’s Only God Forgives, there are stronger connections still with The Act of Seeing, last year’s lavishly produced art book in which Refn drooled over posters for long-forgotten exploitation pictures, mesmerised by the way they “aroused me, shocked me or frightened me”, delighted by their “carny sensibility” and “promises of the impossible”. Those phrases could equally apply to The Neon Demon, a film driven by the same guilty pleasures that have long underpinned Refn’s work, making him both the darling and bête noir of auteur arthouse cinema – the beauty and the beast.

Source: The Guardian